Book examines drawing as a form of reportage

Reportage Drawing – Vision and Experience

Author: Louis Netter

Publication date: January 25, 2024

Format: Paperback

Imprint: Bloomsbury Visual Arts

Illustrations: 55 black and white illustrations

Dimensions: 9 x 6 inches

Series: Drawing In

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

“This book is not only a celebration of the drawing act but also a declaration of its value for documentation.”

With those words, Irish-American artist and scholar Louis Netter aptly introduces his book, Reportage Drawing – Vision and Experience (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2024). Unusual among the narrow range of books available on the subject, the author focuses on the history rather than the how-to of reportage drawing.

Taking an academic approach, Netter examines how drawing has been used from the 19th century to the present day as a form of journalism, especially as it compares to photojournalism. A key principle he examines is the question of objectivity. While acknowledging that the objectivity of photography has certainly been debated, he notes that a photo was once seen as the most objective visual record of an occurrence. By contrast, a drawing, Netter argues, is not intended to be objective. Indeed, it is inherently the subjective view of the artist, and this subjectivity is what defines modern reportage drawing.

“At the core of reportage drawing’s stubborn persistence as a media and practice is our innate connection to the act of drawing,” says Netter, “and how it reflects something fundamental about human vision and understanding.”

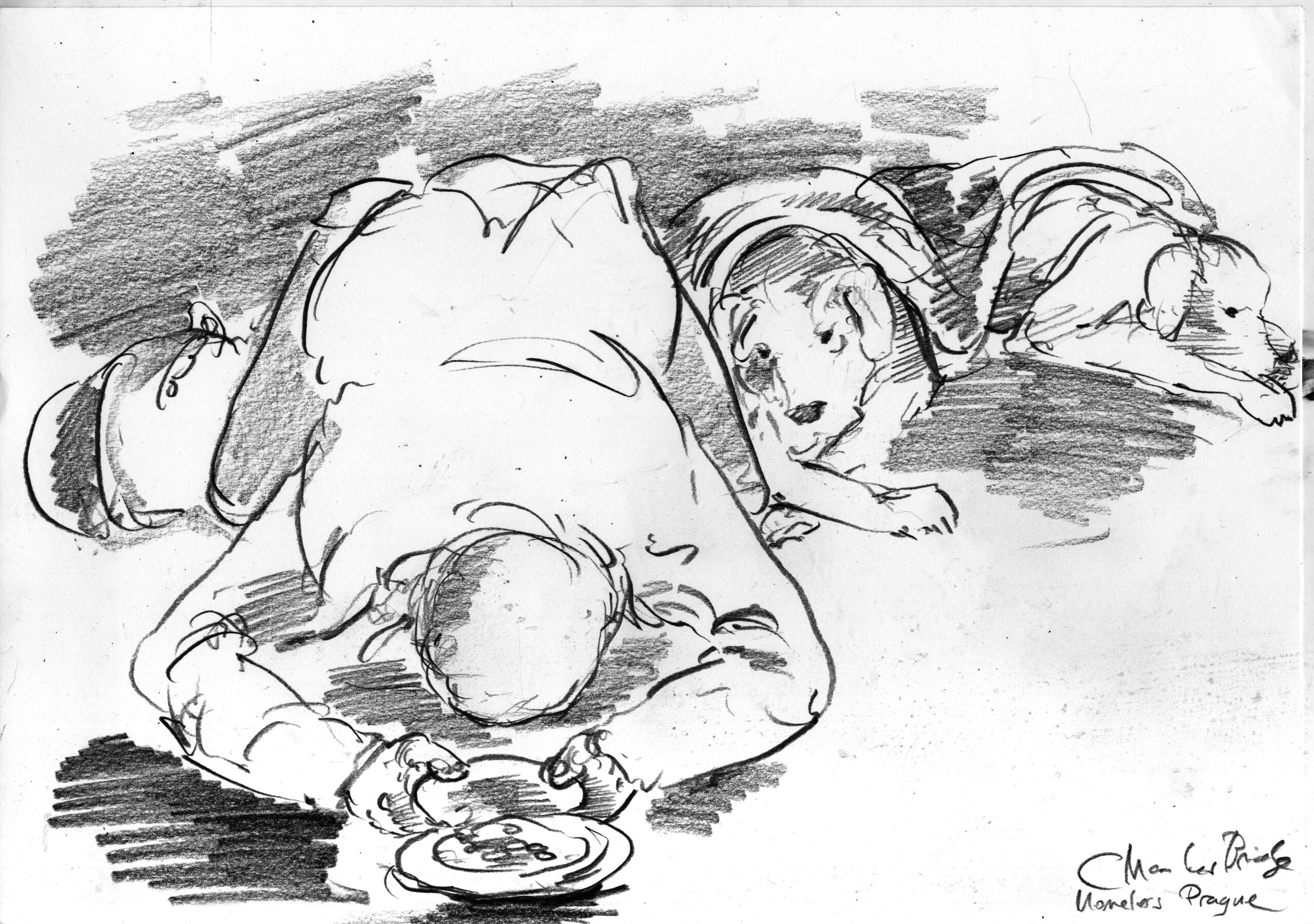

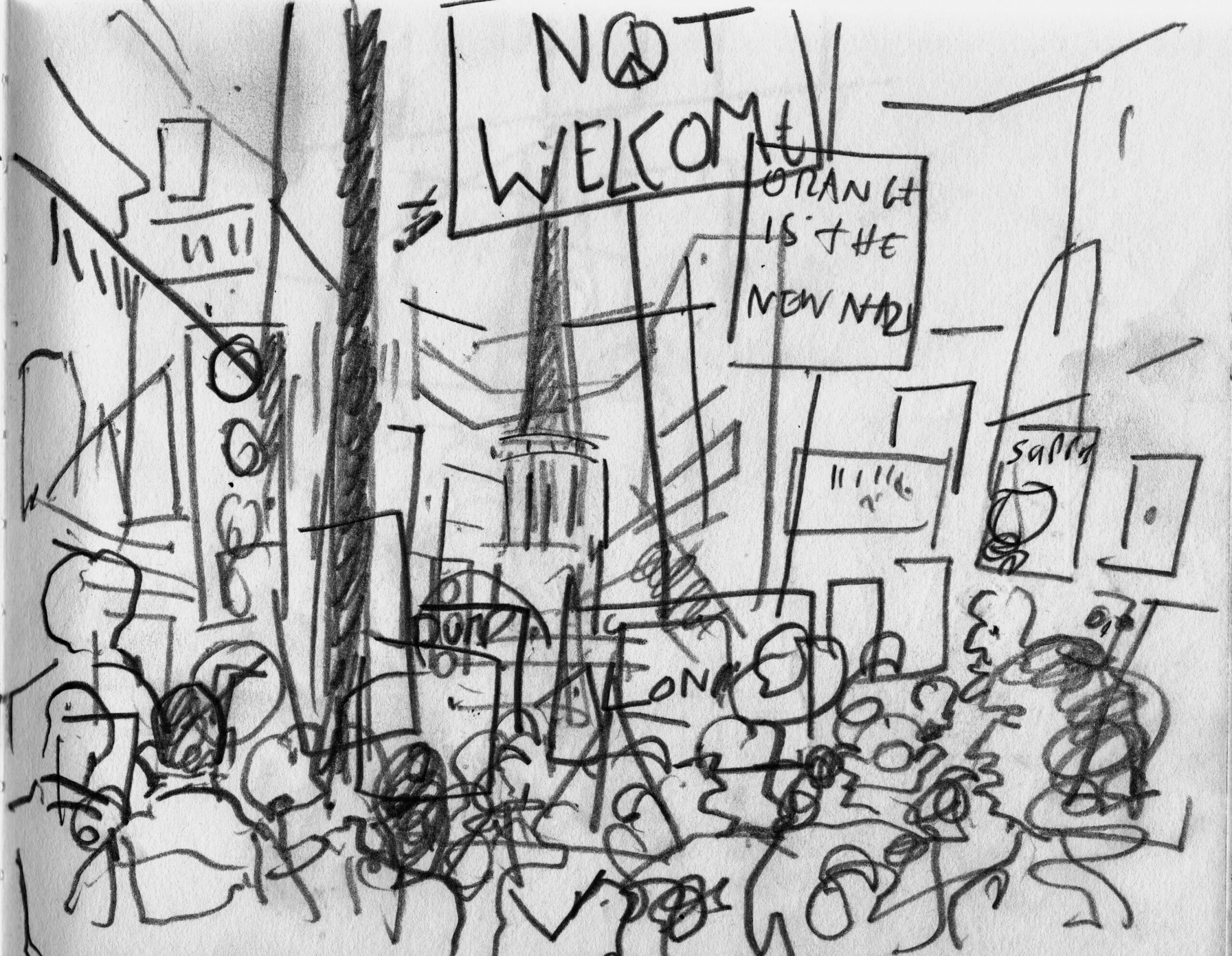

In support of his view, Netter includes case studies of contemporary reportage artists Jill Gibbon, Gary Embury and himself. Gibbon’s experience was particularly intriguing as she recounts making covert sketches while participating in arms fairs for her employer. Using a tiny sketchbook, she recorded sometimes shocking and offensive scenes she witnessed. Her rough, hasty sketches emphasize the surreptitious nature of her experiences.

“One of the things I am increasingly interested in is how physical and visceral drawing is,” Gibbon says. “That you are seeing but with your hands. Your hand understands what the body does more than eye. So, it is a hand understanding of the gesture a camera could never give. . . . And you are discovering through doing it and you can see it in a drawing when that has happened. When it is not the head it is the hand that has seen it. And it is very compelling when you see it. It is felt and seen.”

While the subject matter will be of great interest to many artists and sketchers, Netter’s academic tone is difficult to get through at times. Reportage Drawing is part of Bloomsbury’s Drawing In series of scholarly books that contribute “new perspectives on how drawing facilitates and manifests the production, acquisition and understanding of knowledge.” While I may not be the target audience, journalism students or scholarly readers might have greater patience than I did.

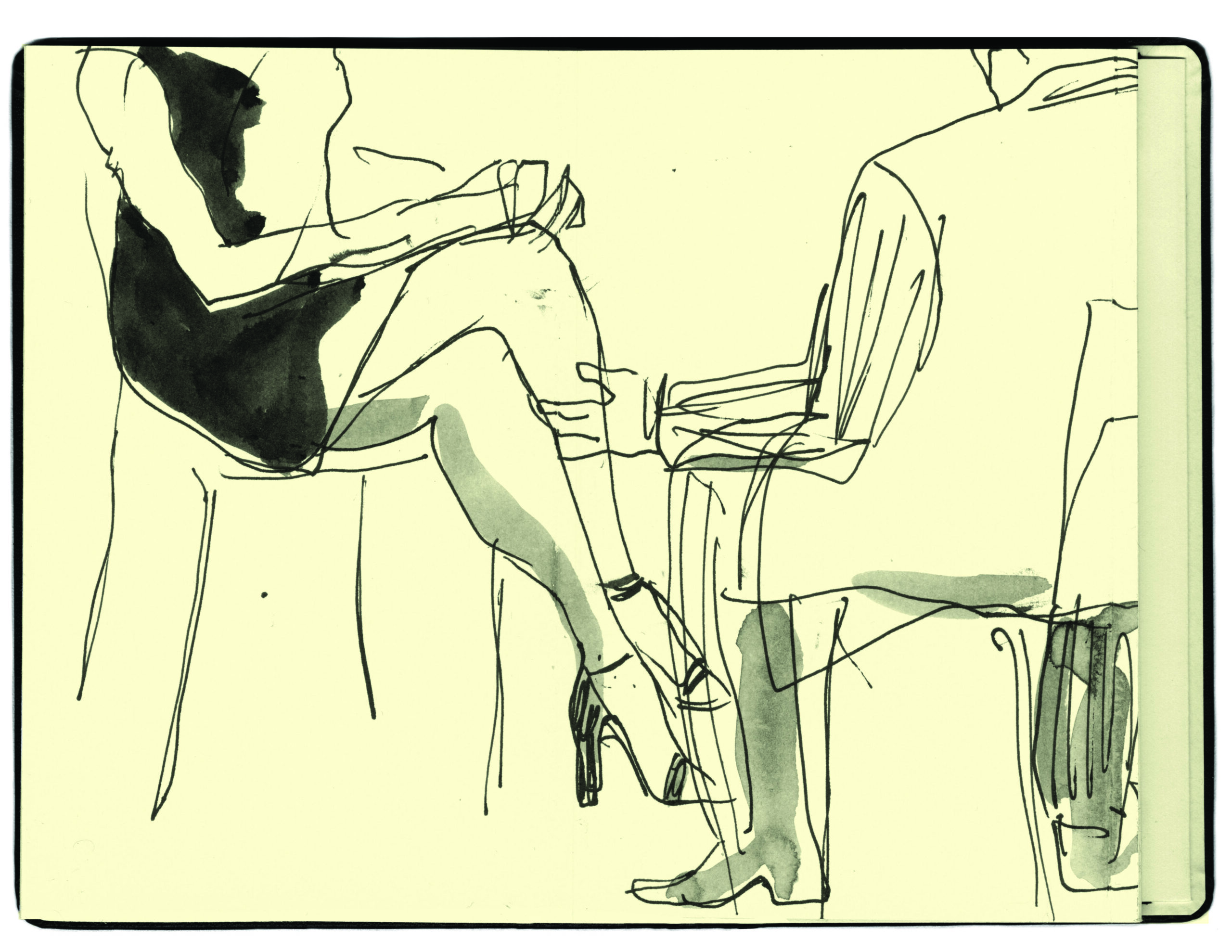

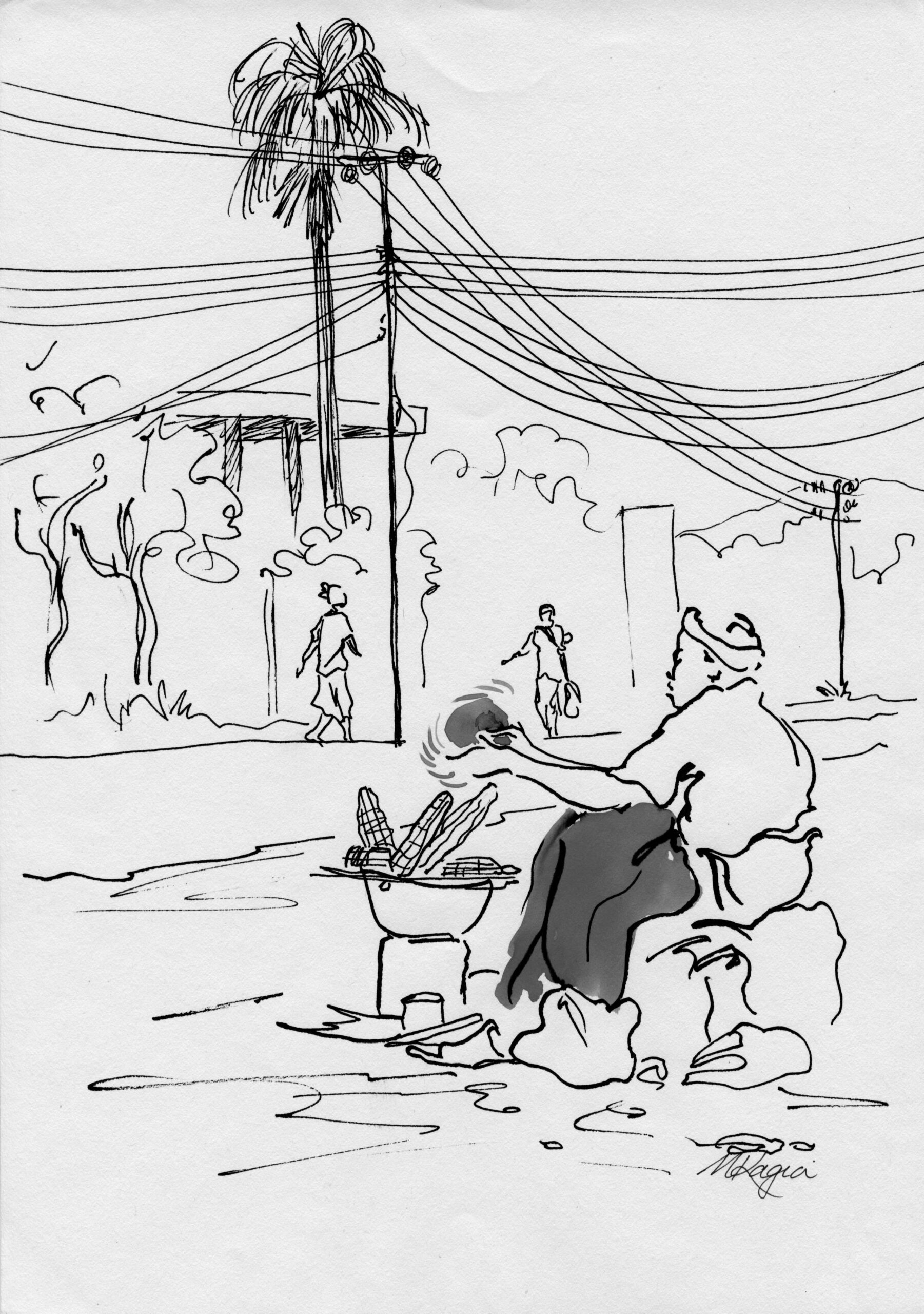

The dry tone, however, is balanced by artist spotlights – interviews with contemporary reportage artists about their practices and including examples of their work. The four artists – Mario Minichiello, Loup Blaster, Mercy Kagia and Dominika Wroblewska – give vivid, passionate recollections of their experiences and relationship to the process, which are compelling and resonant.

I wish Netter had included more examples of artwork, especially in full color (which I assume that at least some featured artists must have used). Reportage Drawing – Vision and Experience is a worthwhile addition to the small field of books on this fascinating and significant topic.

About

On the Spot is the source of information and inspiration for reportage artists, urban sketchers, cartoonists, illustrators and any other visual storytellers who create works of graphic journalism. To become a paid contributor, send your article pitches to editorial@sketcherpress.com.

Print issues

-

On the Spot (Issue 3)

$18.00 -

On the Spot (Issue 2)

$18.00 -

On the Spot (Issue 1)

$15.00